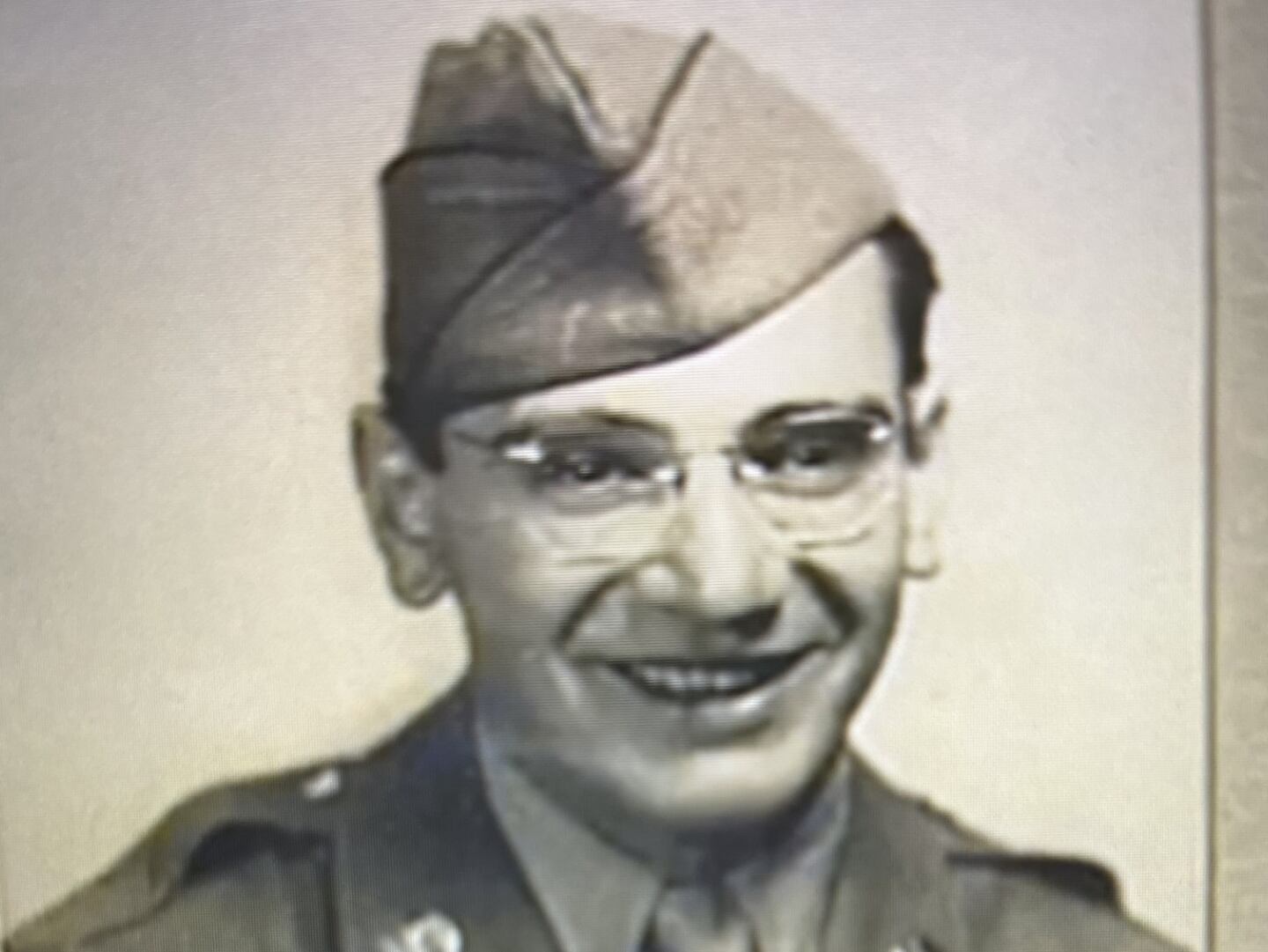

NORTH ATTLEBORO, Mass. — World War II veteran Caster “Cas” Salemi, a longtime Massachusetts resident, will turn 103 this weekend, on Flag Day.

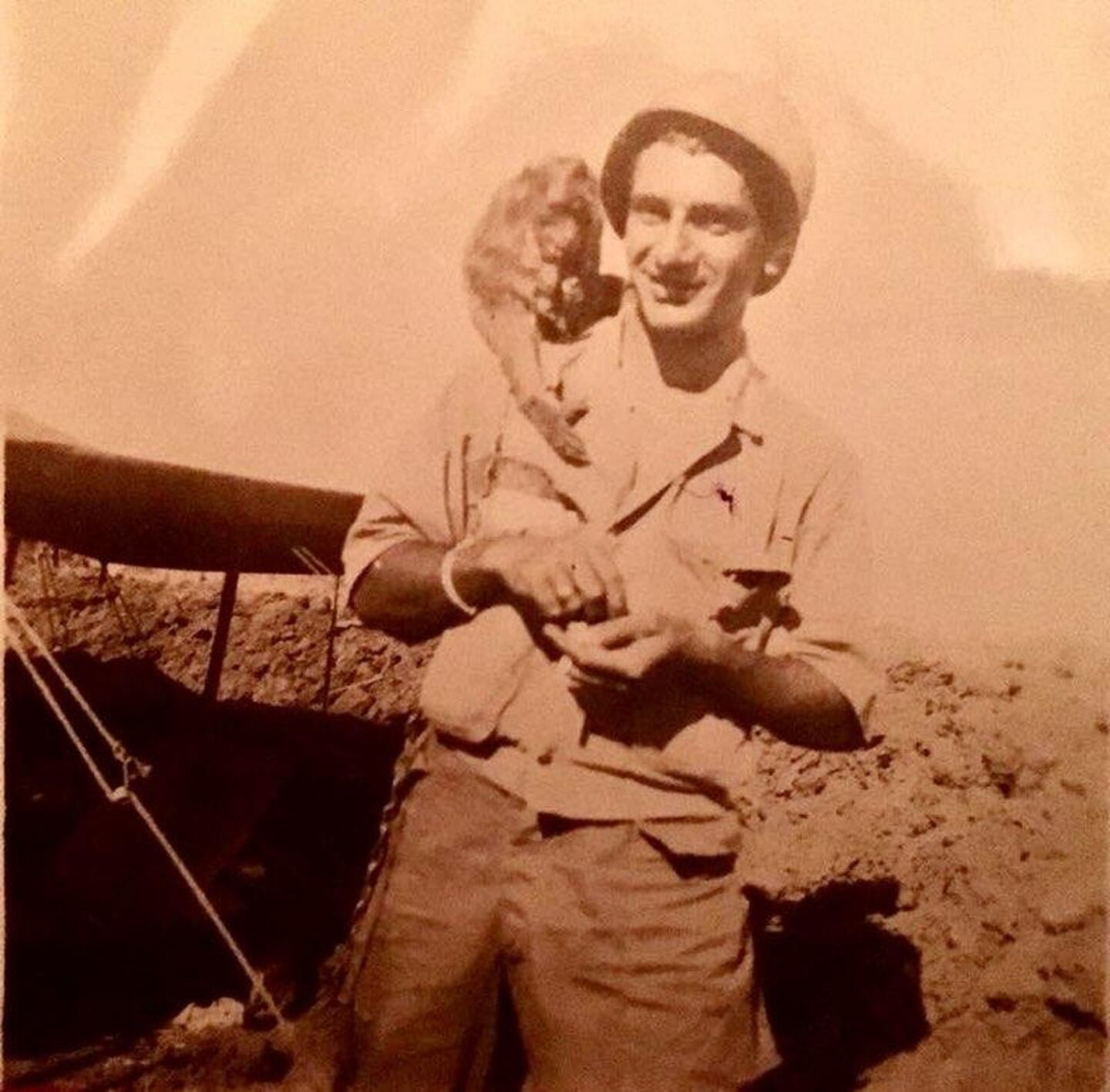

Salemi, of North Attleboro, served in the Army’s 251st Field Artillery Battalion in the South Pacific during the war. He served in two of its major campaigns, New Guinea and the Philippines.

He’s among the few remaining members of American war heroes known as the “Greatest Generation,” said Air Force veteran Natalee Webb-Rubino, who reached out to Boston 25 to share Salemi’s story.

Nearly 131 World War II veterans die each day and of the 16 million men and women who served during the war, just over 100,000 remain, Webb-Rubino said.

“This ‘Greatest Generation’ are a rapidly dwindling sector of Americans that we should honor most reverently,” said Webb-Rubino, a Franklin resident.

OFF TO WAR

After training in Paris, Texas for a year, the 21-year-old Salemi set off on a 30-day ocean voyage to New Guinea.

He had no fresh water on the journey. Soldiers had to wait for rain to shower.

As they neared the coast, soldiers saw lush green fields of grass -- “kunai” grass. Salemi and others had to use their bayonets to cut through the tough, fibrous blades of thick grass to make camp.

At camp, Salemi was handed a can of British Bully Beef (C-Rations) that were from World War I, and manufactured 28 years earlier.

“When we opened the rations, the Palm Trees wilted,” Salemi said, as told to Webb-Rubino.

Having run the enemy off to the West Coast of New Guinea, his unit prepared for their next campaign in the Philippines.

Salemi and the 251st were among the first soldiers to land in Luzon.

As they offloaded the vehicles from their boat, the truck containing all of Salemi’s communications equipment slipped into a sink hole.

With his truck and supplies gone, he had to sit on the beach for three days waiting for their replacement.

DANGEROUS MISSION

In 1941, in Manila, Salemi and his unit provided critical defense, Webb-Rubino said. Over 100,000 Filipino civilians were killed by the enemy.

“Cas and his unit bravely fought the enemy for 165 days without rest,” Webb-Rubino said.

Radio frequencies in the thick jungle terrain of the Philippines would not work and had to be dangerously hardwired.

As a T-4 or Technical Sergeant, Salemi’s job was to lay vital communications wire between the 251st firing batteries and its command base.

He recalled to Webb-Rubino one dangerous mission where his unit had been pinned down in a valley between two mountains under heavy artillery action.

The enemy rolled out cannons from a cave and fired upon the Americans, he said.

With no way out, the men completely disassembled an M90 Howitzer cannon and dragged it across to the other mountain where they could see the enemy’s cave.

“When the enemy once again rolled out their deadly cannons, the soldiers of the 251st were ready and successfully brought an end to the enemy’s carnage in this Valley,” Webb-Rubino said.

In another routine mission, the men positioned their allotted four cannons and created a perimeter around them.

Soon after, they heard and felt the ground rumbling.

The enemy had stampeded a whole herd of carabao, or water buffalo, directly in their path.

“The men ran for cover under the guns, anywhere, just to get away from the animals to avoid death by trampling,” Salemi recalled.

NUCLEAR BOMBS, WAR INJURIES

In 1945, nuclear bombs were dropped on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, on Aug. 6 and Aug. 9, respectively.

Japan surrendered days later, on Aug. 14, 1945.

Salemi was severely injured with “jungle rot,” a condition caused by prolonged exposure to moisture with the inability to keep skin dry leading to a fungal infection.

The North Attleboro veteran could barely walk, covered in the fungus on his hands and feet, he said, as told to Webb-Rubino.

He was medically evacuated on a ship back to the United States. During the 17-day trip home, in the aftermath of Typhoon Queenie, Salemi’s ship experienced sustained winds of 90 mph and rough seas with 50 to 60-foot swells.

While recovering from his severe injuries in California, he and other GIs in his ward heard a strange noise reminiscent of an incoming artillery fire.

The loud noise, which was a jet flying overhead, prompted the soldiers to jump off their beds, Salemi recalled, as told to Webb-Rubino.

They dove underneath them believing they were once again under attack.

To this day, the Massachusetts centenarian remembers bonding with other soldiers “from all walks of life” while serving with them during their darkest hours.

“Learning how to live with others from all different walks of life creates that special bond or camaraderie that soldiers share,” Salemi said, as told to Webb-Rubino.

“We learned to depend on each other which proved to be a critical component in warfare,” Salemi said.

He also compared his wartime service to that of soldiers fighting in the Vietnam War.

“The difference between World War II and the Vietnam conflict was a matter of trust,” Salemi said. “While there was brutality with the Japanese, the soldiers knew where and who they were fighting. The Vietnam Conflict was rifled with distrust and high anxiety.”

“The enemy dug tunnels throughout the Vietnam landscape making it nearly impossible for a soldier to know who, when or where the enemy attacks were emanating from,” Salemi said.

LIFE AFTER THE WAR

Salemi was honorably discharged from the military in 1946.

He was awarded several medals for his service: the Good Conduct, World War II Victory, Asiatic Pacific Campaign (with two stars for the New Guinea and Luzon campaigns) along with an Artillery Pin and the Philippine Liberation medals.

Not long after his discharge, he married the love of his life, Virginia, in 1949.

While he was born on Flag Day, his wife was born on Veteran’s Day.

The couple enjoyed 37 years together and raised two sons and a daughter.

Salemi moved to Massachusetts in 1972 while working for Sylvania Electric Products. He worked in research and development for 39 years through its mergers with GTE which ultimately became Verizon.

A 35-year resident of North Attleboro, Salemi has remained active in several military organizations and is a former member of the town’s Veterans Advisory Board.

He is a Past Commander of the North Attleboro Disabled American Veterans Post 56.

In 2004, Salemi organized and escorted fellow veterans to the grand opening of the World War II Museum in Washington, D.C.

He has also traversed the Honor Flight, a nonprofit organization for veterans to visit memorials built in their honor.

He attributes his longevity to three things: Love what you do, don’t smoke or drink hard liquor, save for an occasional glass of wine; and good genes.

Stories of service are what have inspired Webb-Rubino, who is also a military veteran.

She said she joined the Air Force in 1976, becoming its first female Aircraft Mechanic Crew Chief and while at Kadena Air Force Base in Okinawa, Japan.

In 1999, she founded the 11K road race in Stoneham to honor and recognize veterans. In 2009, she became the City of Melrose’s first female Veterans Service Officer.

“I firmly believe we need to recognize these ‘Greatest Generation’ men and women as often as we can,” she said.

Download the FREE Boston 25 News app for breaking news alerts.

Follow Boston 25 News on Facebook and Twitter. | Watch Boston 25 News NOW

©2025 Cox Media Group